Building a Brute Force Detection Query: How To Think Through Network Logon Failures

All right class, take your seats.

This post is about methodology. How do you go from "I want to hunt brute force attempts" to a query that actually returns useful results? What decisions do you make along the way? And where would you tweak this for your environment?

The Query: What Are We Building?

DeviceLogonEvents

| where TimeGenerated >= ago(30d)

| where ActionType == "LogonFailed"

| where LogonType == "Network"

| where not(ipv4_is_private(RemoteIP)) and RemoteIP !startswith "127."

| summarize FailureCount = count(),

FirstAttempt = min(TimeGenerated),

LastAttempt = max(TimeGenerated),

FailureReasons = make_set(FailureReason),

RemoteIPs = dcount(RemoteIP)

by AccountName, DeviceName, RemoteIP

| where FailureCount > 10

| order by FailureCount desc

| serialize

| extend Rank = row_number()

| extend Award = case(

Rank == 1, "🥇 Top Brute Force IP",

Rank == 2, "🥈 Persistent Retry",

Rank == 3, "🥉 Frequent Failures",

"⚠️ Keep Monitoring"

)

| extend DurationDays = toreal(datetime_diff("day", LastAttempt, FirstAttempt)) + 1

| extend AttemptsPerDay = round(FailureCount / DurationDays, 2)

| project Rank, AccountName, DeviceName, RemoteIP, FailureCount, FailureReasons, AttemptsPerDay, FirstAttempt, LastAttempt, AwardThe goal: find external IPs that are persistently trying to log on to your machines using network authentication, with enough sustained effort to suggest it's not just a misconfigured service.

Why Start with Network Logons?

| where LogonType == "Network"

This was the first real decision. When I think about brute force, most people go straight to RDP attacks, RemoteInteractive logons. That's the obvious one.

But I wanted to look at something a bit different: lateral movement attempts via SMB, admin shares, or PSExec-style access. Those all come through as Network logon types.

Why? Because in environments with decent RDP hardening (NLA, MFA, geo-restrictions), RDP brute force gets blocked fast (most likely, most of you reading this have amended the existing Microsoft built-in templates to exclude failed attempts). But network logons? Those are harder to lock down. Attackers use them for lateral movement once they've got a foothold.

So this query targets a specific attack pattern: external adversaries trying to brute force their way into shared resources. Not the only brute force pattern, but a useful one to hunt.

If your environment has SMB signing everywhere and locked-down shares, this won't catch much. In that case, you'd pivot to RemoteInteractive (tables like SigninLogs) and hunt RDP instead. Different environments, different angles.

Filtering to External IPs: Choosing Your Scope

| where not(ipv4_is_private(RemoteIP)) and RemoteIP !startswith "127."

I filtered to external IPs because I wanted to focus on attacks originating outside the network. Internal logon failures usually mean misconfigured services, broken scheduled tasks, or users fat-fingering passwords. Those are operational issues, not threats.

But here's the trade-off: if you have an insider threat or a compromised internal machine trying lateral movement, this filter hides it. You'd want a second query without this filter to hunt internal patterns separately.

The decision here was: scope the query to one specific scenario (external brute force), so the results stay focused. You can always build more queries for other scenarios.

Aggregating by Three Dimensions

| summarize FailureCount = count(),

FirstAttempt = min(TimeGenerated),

LastAttempt = max(TimeGenerated),

FailureReasons = make_set(FailureReason),

RemoteIPs = dcount(RemoteIP)

by AccountName, DeviceName, RemoteIPThis is where the query gets interesting. Instead of just counting failed logons globally, I grouped by three things: which account, which machine, and which source IP.

Why? Because attackers usually brute-force a specific account on a specific machine from a specific IP. That combination is the fingerprint of the attack.

If you just count failures without grouping, a distributed attack (100 IPs trying 100 accounts) looks the same as one focused attack. By grouping this way, the focused attack stands out clearly as one row with high failure counts.

The FailureReasons = make_set(FailureReason) line is useful too. It collects all the reasons the logon failed. "Invalid username" means they're guessing accounts. "Account locked" means they triggered the lockout policy. "Password expired" means something's misconfigured. Each reason tells a different story that you can use for further investigation and locking down your precious environment.

The Threshold: Where You Tune for Your Environment

| where FailureCount > 10

Ten failures is deliberately low. Why? Because I wanted to see what patterns emerged first, then tune the threshold up based on results.

In practice, 10 failures over 30 days catch a lot of noise, broken services, failed automation, and misconfigured backups. You'll get false positives.

If you're using this in production, start higher. Try 50 failures over a week. Or better: look at the AttemptsPerDay column and filter where that's above 5. Sustained daily pressure is harder to explain away as operational noise.

The threshold is the knob you turn based on your environment. High-volume environment with lots of service accounts? Turn it up. Small, quiet network? Leave it low and investigate everything.

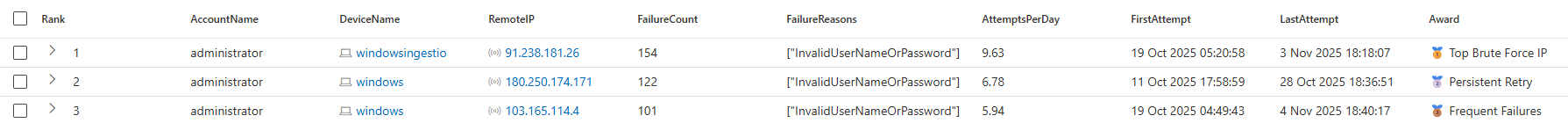

The Fun Part: Emoji Awards

| extend Award = case(

Rank == 1, "🥇 Top Brute Force IP",

Rank == 2, "🥈 Persistent Retry",

Rank == 3, "🥉 Frequent Failures",

"⚠️ Keep Monitoring"

)This section is completely unnecessary for detection. It's there because it makes the output fun to look at and easy to communicate.

When you drop this in a dashboard or show it to someone, the emoji medals immediately draw their eye to the top offenders. It's visual shorthand for "this one matters most."

Does it add security value? No. Does it make the data easier to parse at a glance? Absolutely. Sometimes that matters.

It also shows you the countless possibilities you can achieve when you know how to use KQL. Building new columns and cases can be rewarding in multiple other detections

The Key Metric: Attempts Per Day

| extend DurationDays = toreal(datetime_diff("day", LastAttempt, FirstAttempt)) + 1

| extend AttemptsPerDay = round(FailureCount / DurationDays, 2)This is the line that turns raw counts into something we can actually work with.

An IP with 100 failures over 30 days is 3.3 failures per day. That's probably a broken service retrying periodically.

An IP with 100 failures over 2 days is 50 per day. That's sustained effort. That's an attack.

The rate tells you intent. Count alone doesn't. Try to calculate the rate when you're hunting patterns over time.

The + 1 in the calculation ensures you don't divide by zero if FirstAttempt and LastAttempt are the same timestamp - so if all logon attempts happened at the same moment you'd end up with a zero days difference. Adding +1 guarantees you always divide by at least one day, so the math never blows up.

What This Query Actually Does Well

It finds focused brute force attempts: external IPs targeting specific accounts on specific machines with sustained pressure over days. That pattern is hard to fake. It's hard to hide. It suggests intent.

It also filters out a lot of noise by scoping to Network logons and external IPs. You get fewer results, but the results you get are more meaningful.

What It Doesn't Catch

This query won't catch distributed attacks where the attacker uses hundreds of IPs to try hundreds of accounts. Each IP only tries once, so your threshold filters it out.

It won't catch RDP brute force, because those are RemoteInteractive logons, not Network.

It won't catch internal attacks, because private IPs are filtered out.

It won't catch attackers who succeed quickly; if they guess the password on their second try, you see two failures, then a success, but your threshold might miss it.

These aren't flaws. They're deliberate scope choices. Every query trades breadth for precision. This one leans toward precision.

How You'd Use This

Run it weekly. Look at the top results. Ask: Do I recognise this IP? Is this a known service? Is this a real attack?

For anything suspicious, dig deeper: look for successful logons from the same IP within an hour of the failures. That's your smoking gun.

You can also pair this with a blocklist automation: if an IP hits your threshold, automatically block it at the firewall while you investigate.

Or drop it in a Sentinel workbook: visualise the top offenders over time, track whether the same IPs keep appearing week after week.

The Methodology: How You'd Build Your Own Version

Start with the attack pattern you care about. For me, it was external adversaries trying network logons. For you, it might be RDP attempts, internal lateral movement, or service account abuse.

Choose your filters to match that pattern. What logon type? What IP range? What timeframe?

Aggregate by the dimensions that define the attack. Account + machine + IP? Just IP? Account + time of day?

Calculate a rate metric, not just a count. Attacks have tempo. Misconfiguration is random. Rate separates them.

Tune the threshold based on real results. Start low, see what you get, adjust upward until you're seeing 5-10 results that actually matter.

That's the process. The query itself is just the output.

Why Share This?

Because breaking down how queries get built is more useful than just sharing the final code. You see the decisions. You see the trade-offs. You see where you'd change it for your own use case.

This isn't the "right" way to hunt brute force. It's one way. Take what's useful, change what doesn't fit, build your own version.

Class dismissed.