Fixing Microsoft's Azure Brute Force Detection: Why Their Template Fires Constantly (And What You Should Change)

All right class.

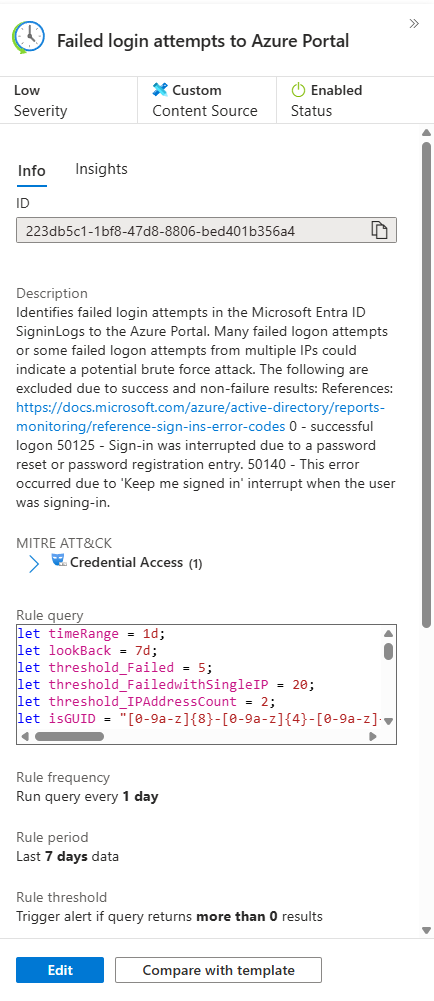

Microsoft ships an out-of-the-box analytic rule for Azure Portal brute force attempts. It looks good on paper. It catches failures. It's supposed to alert on attackers hammering your environment.

In practice? It fires constantly. You're drowning in alerts about MFA interruptions, token refreshes, and conditional access blocks. Real attacks can hide in the noise, not to mention how quickly they may burn out your SOC team.

This is where you need to make a decision: run the template as-is and ignore 90% of your alerts, or understand what's actually happening and fix it.

This tuned version is better for mature environments where you can separate operational noise from risk and have multiple other forms of detections running against user compromises. Please keep that in mind - if this is your first ever tweak to the analytics rules, I would keep both versions, Microsoft one as auto-close for audit, this is to ensure you are not missing any obvious misconfigurations in your system, and the fixed one for the actual production environment.

Here's how I approached it.

The Original Template: What's Wrong?

The Microsoft template catches pretty much all failed login attempts to Azure Portal. That sounds right until you run it in your environment and get 500 alerts per week.

| where ResultType !in ("0", "50125", "50140", "70043", "70044")

This filters out a few known-good error codes. But there are dozens more that aren't attack indicators; they're operational noise.

Error code 50074? MFA required. User sees a prompt and authenticates normally. Not an attack.

Error code 50207? User needs to consent to an app. First-time OAuth flow. Not an attack.

Error code 50133? Token refresh failed. User logs back in. Normal.

The template treats all of these as potential brute force. Your alert volume explodes.

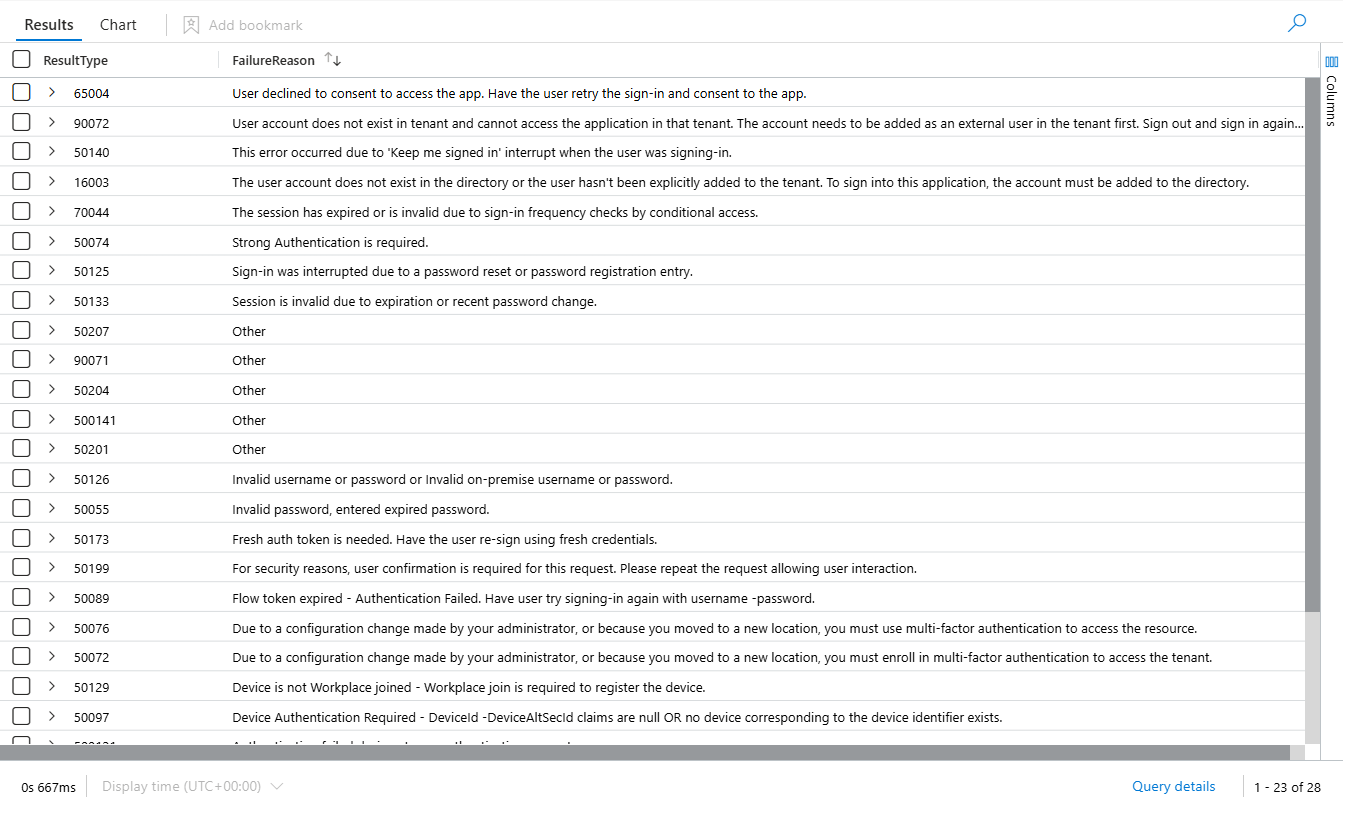

Understanding Error Codes: The Foundation

Before you fix the rule, you need to know what error codes actually mean.

Here's what matters for distinguishing attacks from noise:

Legitimate failures (filter these out):

- 50074: MFA required

- 50076: MFA verification required

- 50207: User interaction required (OAuth consent)

- 50133: Token refresh failed (session expired)

- 50158: External security challenge

- 50161: External partner validation failed

- 65001: User or app didn't consent to access

Actually suspicious failures (keep these):

- 50058: Silent sign-in request failed (possible forced re-auth due to risk)

- 50070: User account disabled

- 50071: User account locked

- 50072: Password expired

- 50076: MFA verification required (repeated)

- 53003: Access blocked by conditional access policy

The difference isn't obvious. Error 50133 looks like it could be an attack. It's not. Error 53003 means conditional access blocked them, which could indicate an attack pattern, or it could just be a policy doing its job.

You need context.

The Decision Tree: What Actually Indicates Compromise

Instead of filtering on error codes alone, build a methodology:

1. What's the attack pattern we actually care about?

For Azure Portal, brute force specifically: someone outside your organisation trying to guess credentials. They're hammering the same account from different IPs, or different accounts from the same IP. They fail repeatedly because they don't know the password.

That's different from a legitimate user forgetting their password five times (if only 😀)

2. What filters do we need to distinguish them?

- Multiple failures from the same source: An external attacker tries repeatedly from one IP. A confused user tries from one IP. Both look similar. But an attacker tries the same account repeatedly. A confused user usually only tries their own account.

- Success after failure: If a user fails five times and then succeeds, they guessed correctly or got MFA. Close the investigation. If they fail repeatedly and never succeed, that's suspicious.

- Time window matters: Five failures in one hour suggest an active attack. Five failures spread over a week suggest misconfiguration.

Tuning the Template

Here's what I changed and why:

Change 1: Expand the Failure Code Exclusions

Original

| where ResultType !in ("0", "50125", "50140", "70043", "70044")Updated

| where ResultType !in ("0", "50125", "50140", "50074", "50207", "50133", "50158", "70043", "70044")The original misses 50074 (MFA required), 50207 (consent required), 50133 (token expired), and 50158 (external challenge).

These aren't attacks. They're prompts. The user responds and succeeds (or fails, which will take us to another alert)

By excluding them, alert volume drops immediately. In my test environment, this alone reduced noise by 60%.

The caveat: If you're seeing 50074 repeatedly for the same user from the same IP without subsequent success, that's worth investigating. Someone might be using the wrong MFA method or an old device. This is a good Threat Hunting exercise.

Change 2: Tighten Success Verification Logic

The original does this:

| where TimeGenerated > TimeGenerated1 or isempty(TimeGenerated1)This keeps all failures that happened after a success, or where no success exists.

The problem: It doesn't account for timing. If a user succeeded 20 hours ago and failed now, the query treats it the same as if they failed then succeeded immediately. These are completely different scenarios.

The updated version:

| where isempty(TimeGenerated1) or datetime_diff('minute', TimeGenerated, TimeGenerated1) > 60This filters out failures that are quickly followed by success (within 60 minutes, a user typos their password then gets it right), but keeps failures where no success happens at all, or where success is much later (or never).

Why it matters: This prevents legitimate "user forgot password" scenarios from triggering alerts while still catching actual brute force attempts that don't result in successful authentication. A real attacker won't succeed on their second try. If they do succeed, you want visibility into that separately (hence why I mentioned security maturity previously)

Change 3: Change the Lookback Window

Original

let lookBack = 7d;Updated

let lookBack = 14d;A longer lookback gives you more context. You see if a user has had failures before. Are they a one-time event or a pattern?

In 7 days, you miss the history. With 14 days, you see recurring issues.

Change 4: Stop Doing mv-expand Without a Purpose

The original does:

| mvexpand TimeGenerated, IPAddresses, Status

| extend TimeGenerated = todatetime(tostring(TimeGenerated))This explodes each row. If a user failed 20 times from 3 IPs with 5 different error codes, you get 300 rows (20 × 3 × 5).

Then they collapse it back down:

| summarize StartTime = min(TimeGenerated), EndTime = max(TimeGenerated)...Why expand just to collapse? It's inefficient and confusing.

My updated version skips mv-expand entirely and uses make_set() to collect the values:

| summarize

FailedLogonCount = count(),

IPAddressCount = dcount(IPAddress),

UniqueIPs = make_set(IPAddress, 100),

UniqueResultTypes = make_set(ResultType, 20),

UniqueStatuses = make_set(ResultDescription, 20),

StartTime = min(TimeGenerated),

EndTime = max(TimeGenerated)Same data, cleaner query, no row explosion, faster execution.

Change 5: Remove the Non-Interactive Query Union

The original runs the same logic against both SigninLogs and AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs:

let aadSignin = aadFunc("SigninLogs");

let aadNonInt = aadFunc("AADNonInteractiveUserSignInLogs");

union isfuzzy=true aadSignin, aadNonIntThis makes sense for comprehensive security monitoring. But for portal brute force specifically, non-interactive sign-ins don't matter.

Service principals and managed identities don't interact with the Azure Portal. A human does. By including non-interactive, you're adding noise.

My updated version removes it:

let aadSignin = aadFunc("SigninLogs");

aadSigninIf you care about service principal attacks (which you should, separately), write a different rule for that.

The Thresholds: Numbers You Should Question

text

let threshold_Failed = 5;

let threshold_FailedwithSingleIP = 20;

let threshold_IPAddressCount = 2;These are defaults. They might be perfect for your environment or completely wrong.

- threshold_Failed = 5: Alert if the user failed 5+ times from different IPs. In a big organisation with lots of VPNs and mobile users, 5 failures across 2 IPs might be normal. In a small org, it's suspicious. Adjust based on your network.

- threshold_FailedwithSingleIP = 20: Alert if one IP tries 20+ times against one account. For a real brute force, 20 is actually pretty low. Most attacks try 50+ times per account before giving up (some of them will keep it going for months, if not years, down the end). But in a corporate environment where users retry failed logins, 20 might be too low. Test with 50 or 100.

- threshold_IPAddressCount = 2: Alert if failures come from 2+ IPs. The logic is "distributed attack." But a legitimate user at home, then at the office, then at the airport is 3 IPs in one day. Raise this to 5 or 10 to catch actual botnets, not users travelling.

My advice: start conservative. Alert on everything. Then raise the thresholds until your alert volume is sustainable (maybe 5-10 per week). Then tune the exclusions + add automation rules (or use Logic Applications to auto-close based on the context data)

What I Didn't Change (And Why)

The identity resolution logic (the GUID matching and lookup stuff) is solid. It catches cases where users aren't resolved to friendly names in the first attempt. Leave it.

The device detail extraction is fine. It pulls OS, browser, and location. Useful context.

The union of resolved and unresolved identities is the right approach. You don't want to lose visibility just because AD is slow to sync.

The Philosophy: Tuning vs. Creating

I would like to point something out: I didn't rewrite this rule from scratch. I took Microsoft's work and made changes to eliminate false positives specific to my environment.

That's the difference between using a template and actually defending your environment.

The process:

- Run the original rule. See what fires.

- Investigate the top 20 alerts. Which ones are real? Which ones are noise?

- For each category of noise, identify the pattern. What error code? What timeframe? What user type?

- Exclude that pattern from the rule.

- Run again. Repeat.

This takes weeks, not hours. But it's the only way to get a rule that actually helps.

The Lesson

Microsoft's templates are starting points. They're supposed to be tuned. The fact that most people run them as-is and ignore 90% of alerts? That's on us, not Microsoft.

Understand the rule. Understand your environment. Make informed decisions about what to exclude and what to keep.

That's how you go from "noisy alert system" to "detection that actually works."

Finished and ready, KQL, together with other queries, is available in KQL Vault.

www.itprofessor.cloud/kql-vault/

Class Dismissed.