The KQL Playbook (Play #1): A Beginner's Guide to Talking to Your Data

Alright, class. You've done it. You've deployed Sentinel, you've connected your data, and you've even investigated your first incident. You feel like you're on top of the world. Then you click on the Logs blade, and your heart sinks.

It's just... a blank, white box. A blinking cursor, mocking you.

This is the moment every new SOC analyst faces. The moment you realise that all the world's security data is at your fingertips, but you don't know the magic words to ask it questions.

That, my friends, is where KQL comes in. And today, we're going to learn the magic words.

📚 The Complete KQL Playbook Series

You're reading part of The KQL Playbook, a comprehensive five-part journey from KQL beginner to threat-hunting professional. Whether you're just starting out or levelling up your detection skills, each play builds on the last.

The Five Plays:

Play #1: A Beginner's Guide to Talking to Your Data

The pipe (|), where, summarize, project, and sort by. The foundational moves that turn a blank query window into your first real conversations with data.

Play #2: Mastering the Matching Game

The difference between == and =~, when to use has vs. contains, and why one wrong character can blind your entire detection strategy.

Play #3: Taming Messy Dataparse, extract, split, bin, and mv-expand. Your toolbox for wrestling chaotic strings, timestamps, and JSON objects into submission.

Play #4: The Correlation Play: Joining Tables and Enriching Data

Master let, join, and the art of connecting disparate log sources to build complete narratives of attacker movement.

Play #5: The Anomaly Play: Finding the 'Weird'make_set, set_difference, and arg_max. Your weapons for hunting threats you don't already know about.

Jump to Your Level:

Beginner? Start with Play #1

Getting zero results? Play #2 has the answer

Drowning in messy data? Play #3 fixes that

Need to correlate events? Play #4

Ready to hunt anomalies? Play #5

Remember: Don't try to memorise syntax. Master the mindset. Every complex query is just these fundamentals chained together with pipes.

So, What the Heck is KQL?

KQL stands for Kusto Query Language. "Kusto" was the internal name used by Microsoft for Azure Data Explorer, which also uses KQL. Think of KQL as a language, just like English or Polish, but its only purpose is to have a conversation with massive piles of data. It's used across the entire Azure ecosystem—Sentinel, Defender, Log Analytics—so learning it is less of a suggestion and more of a career superpower.

Forget the corporate history. All you need to know is this: KQL is how you ask your logs questions. Simple as that.

The Golden Rule: The Mighty Pipe |

Before we write a single query, you need to understand the single most important character in the entire language: the pipe (|).

If you see a query that looks like this...

SomeTableName

| where TimeGenerated > ago(1d)

| summarize count() by UserName

| sort by count_ desc...your brain probably short-circuits. But here's the secret. The pipe | just means "and then..."

Let's read that query again in plain English:

- Get me everything from

SomeTableName... - and then... filter it to only show stuff from the last day.

- and then... count how many events there are for each user.

- and then... sort it so the user with the most events is at the top.

See? It's not magic. It's a recipe. It's a production line. Each | is a new station on the assembly line that does one specific job. These are the fundamentals that turn KQL from scary gibberish into a logical set of steps.

The KQL Starter Pack: Verbs You'll Actually Use

Let's learn the verbs you need to have your first conversation. We'll use real-world SOC scenarios, not some textbook nonsense about fruit.

1. where: The Bouncer

The where operator is the bouncer at the door of your club. Its only job is to filter out the stuff you don't want. It is, without a doubt, the operator you will use more than any other.

Scenario: The CISO just ran into the room, coffee flying everywhere, yelling that he read an article about Russian hackers. He wants to know if anyone has tried to log in from Russia in the last week.

// We're looking at the SigninLogs table from Entra ID

SigninLogs

| where TimeGenerated > ago(7d)

| where Location == "NK"In English: "Get me the SigninLogs, then filter for the last 7 days, then filter again to only show logins where the location is 'NK'."

2. summarize: The Bean Counter

Okay, so you've filtered your data. Now you want to group it and count it. summarize is your bean counter. It's perfect for finding patterns, like "how many times did this thing happen?"

Scenario: Your "Failed Logins" alert is going nuts. Is it one person who forgot their password, or is it a brute-force attack against many accounts?

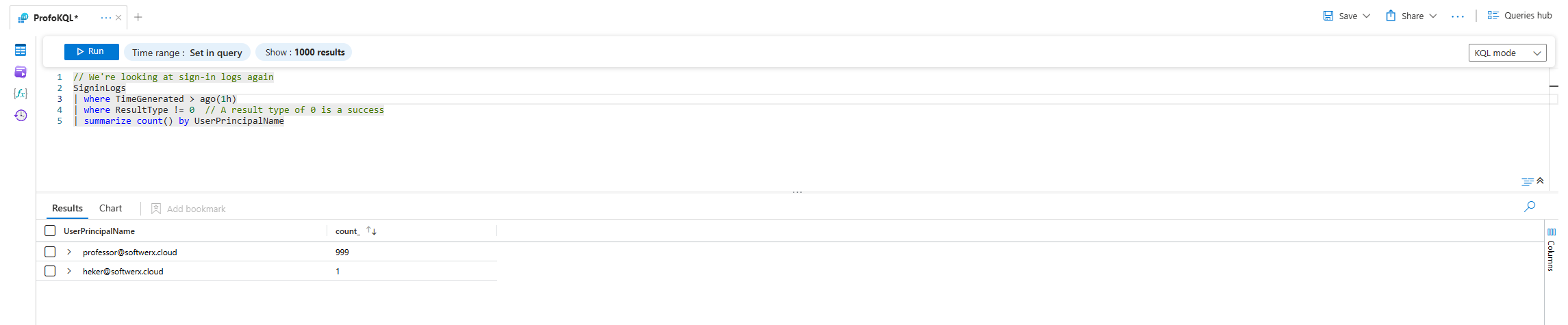

// We're looking at sign-in logs again

SigninLogs

| where TimeGenerated > ago(1h)

| where ResultType != 0 // A result type of 0 is a success

| summarize count() by UserPrincipalNameIn English: "Get the sign-in logs, then filter for the last hour, then filter for only the failures, then give me a count of those failures for each unique username (by UserPrincipalName)."

Now, instead of a million log entries, you'll get a clean table:

Yeah. I think we found our problem.

3. project: The Neat Freak

Your queries can return dozens of columns, most of which are useless noise. project is the neat freak that tidies up your results, letting you choose only the columns you care about.

Scenario: You've found the brute-force attack from the last query. Now you need to give your network team a list of the attacker's IP addresses to block. They don't care about a timestamp or a correlation ID; they just want the IPs.

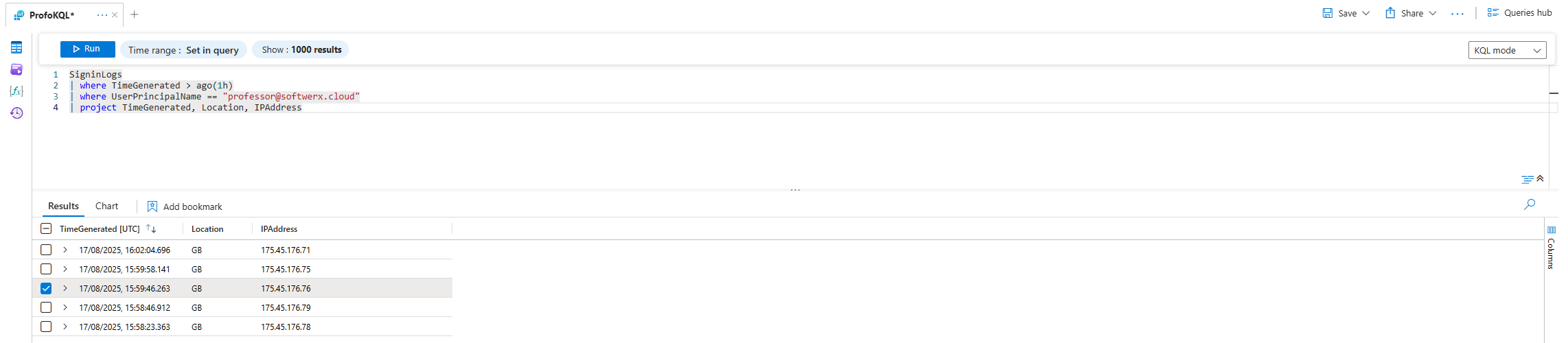

SigninLogs

| where TimeGenerated > ago(1h)

| where UserPrincipalName == "professor@softwerx.cloud"

| project TimeGenerated, IPAddress, Location

In English: "Get the sign-in logs, then filter for our attacker in the last hour, then throw away all the columns except for TimeGenerated, IPAddress, and Location."

4. sort by / top: The Leaderboard

Sometimes you don't want to see everything; you just want to see the top offenders. sort by will order your results, and top is a convenient shortcut.

Scenario: Let's find the top 10 chattiest devices on our network. Which machines are sending the most logs? Maybe one is misconfigured, or maybe it's infected and screaming for help.

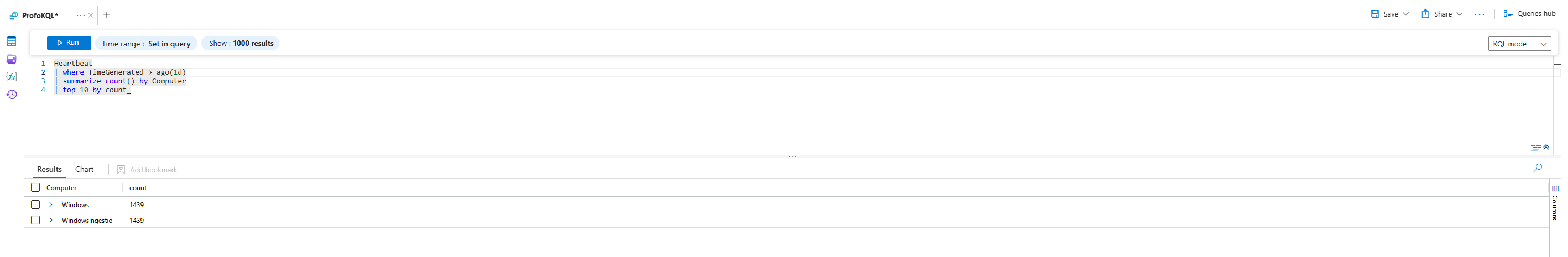

// We're looking at the Heartbeat table from the Azure Monitor Agent

Heartbeat

| where TimeGenerated > ago(1d)

| summarize count() by Computer

| top 10 by count_

In English: "Look at all the agent heartbeats from the last day, then count them up for each computer, then show me only the top 10 computers with the highest counts." (top 10 by count_ is just a cleaner way of saying sort by count_ desc | take 10).

Putting It All Together: A Real Mini-Investigation

Let's combine these.

The Mission: "Find the single user account that has had the most failed logins from different IP addresses in the last 24 hours. Show me the username, how many times they failed, and from how many unique locations."

SigninLogs

| where TimeGenerated > ago(24h)

| where ResultType != 0

| summarize FailedLoginCount=count(), UniqueIPs=dcount(IPAddress) by UserPrincipalName

| sort by FailedLoginCount desc

| top 1 by FailedLoginCountLet's break down that summarize line:

FailedLoginCount=count(): We're counting the total failures and naming the new columnFailedLoginCount.UniqueIPs=dcount(IPAddress): We're getting a distinct count of IP addresses and naming that columnUniqueIPs.by UserPrincipalName: We're grouping all this by the username.

That one query tells a powerful story. If a user has 1,000 failed logins from 1 unique IP, they probably just forgot their password. If they have 1,000 failed logins from 500 unique IPs, that account is under attack.

Class, don't try to memorise a hundred different KQL operators. Master these first few. Every complex, terrifying-looking query you'll ever see is just a combination of these simple building blocks, chained together with the mighty pipe (|).

Your homework is to open the Logs blade in Sentinel, pick any table, and just start asking it questions. Start with where, add a summarize, and clean it up with project. This isn't a dark art; it's a conversation. And you've just learned how to say "hello."